|

| Out of the shadows comes Klaus Kinski ... |

|

| And then the credits come: |

[Note:

This is the twentieth post in a continuing series discussing and analyzing

all the Krimis and Gialli I've seen. As with every post on this site, SPOILERS SHOULD BE EXPECTED.]

My Krimi Rating: ★★★½ (out of 5★)

Subcategory (if any):

i. Heist / Master Criminal Krimi

ii. Arent-as-Comedy-Routine Krimi

iii. Kinski-as-Grotesque Krimi

Who Portrays the Detective (amateur or official):

Heinz Drache (official)

Who's the Ingénue:

Doesn't have one

In My Krimi Top 20 (Y/N): Yes (Letterboxd link)

In my review of Vohrer's MAN WITH THE GLASS EYE (1969), I wrote this:

"If the major weakness to be found in the black-and-white [Krimis] is their tendency to go hamfisted and stupidly happy into comedy schtickdom, then the major weakness of the color entries is that they water down or ignore the touchstones of the genre in a wrong-footed attempt to 'update' the work for an increasingly less-censored 60s era."It's the first point—the Krimi's uneasy relationship with its comedic elements—that serves, I think, as one of the primary stumbling blocks to people trying to get into the genre for the first time. (Two other stumbling blocks—coming to the Krimi backwards [i.e., after one has already discovered the Giallo] and the mash-up worldview the movies present—is covered in the brief review of THE CREATURE WITH THE BLUE HAND.)

That is, sometimes the movies are just too goofy for their own good. Broadly, ridiculously comedic. Full of pratfalls that feel like they belong in vaudeville. The broadest forms of this humor are usually concentrated in whatever character Eddi Arent plays (they certainly are here, in DER ZINKER). And the viewer's ability to accept (or simply not mind) whatever comedy-level his character gets turned up to goes hand-in-hand with the ability to "believe" the peculiar, particularly drawn world these movies inhabit.

There *are* roles that show Arent's ability to integrate the required comedy elements in human and organic ways—I've always found his dance sequence in the Club Mekka (in 1962's THE INN ON THE RIVER) to be charming, even endearing (for me it has something to do with the fact that he's clearly taxing himself physically in order to keep up with the dance, and he seems to get genuine joy out of the challenge). As well as the way that he feigns a breathless happiness in order to deliver a secret message to Brigitte Grothum's character shortly after this.

(One might ask at this point: Why did the producers feel that such a pronounced level of comedy *was* required? What production and/or cinematic history required this aesthetic choice at the cost of all others? Are the works of Wallace full of cartoonish interludes of characters mugging through scenes and taking pratfalls? I have no idea.)There are also the handful of times when Arent's schmuckish persona is used to mask a nasty streak, the Arent-as-villain subcategory you can find in these movies. Whether it's his reveal as the callous, knife-throwing mastermind in CIRCUS OF FEAR (1966), or the killer priest in THE HUNCHBACK OF SOHO (also 1966), where his hollowly held belief is the collar he wears to hide his identity from the cops. The best version of this plot twist (which itself became, for a few years, its own, new Krimi convention) comes in 1965's THE SINISTER MONK, where Arent's puppy-dog concern for Karin Dor's character masks (and contradicts) his identity as a money-grubbing, white-slaving criminal mastermind. His performance, esp. his screen presence in the final scene, feels nuanced, infused with an almost tragic sense of sadness. I'm not sure he's been better anywhere else.

Too often, though, his antics seem so tonally off-putting, so insufferable and disrespectful of the suspension of disbelief, that it amounts to a deal-breaker (for that particular Krimi to succeed as a film). This is one reason I don't rate the otherwise drenched-in-style Vohrer film THE INDIAN SCARF (1965) more highly in the canon. I find it especially grating when they extend this eye-rollingly stupid humor to the last shot of the film, in the form of the fourth-wall-breaking "Ende gag" (see, for example, the way Arent yuks it up—and thereby kills all the weirdo dramatic weight conjured by Dieter Borsche's psychotronic freakout—at the end of 1963's THE BLACK ABBOT).

(The other form that comedy takes in these films, other than Arent, is usually tied to secondary characters, or to certain hijinks-heavy comedic situations. For discussion of this re: DER ZINKER, see the stuff about Agnes Windeck's character below.)Having said that, evaluating any Krimi comes down to a pretty standard formula for me:

There are any number of recognizable conventions that each movie can choose to mix-and-match in the making of its plot (conventions I've begun to break down in the "Subcategories" field at the beginning of each review). Their success or failure (for me at least) usually hinges on:

- Which combination the filmmakers choose, and

- the style and/or ingenuity and/or transgression they bring to bear on the way the conventions get deployed.

(Add to the subcategories above two more mitigating factors in the enjoyment of these movies: the strength and weirdness of the score and one's personal taste when it comes to casting. [As I mentioned to Craig Clark, when he asked my thoughts on THE RETURN OF DR. MABUSE, "Gert Fröbe + Lex Barker + Daliah Lavi will always be 'lesser than' Joachim Fuchsberger + Karin Dor + Klaus Kinski". I.e., some Krimi actors are inherently more interesting to me than others.] Peter Thomas' main ZINKER theme is a kind of frantic, doot-doot-duh-doot beat counterpointed by long, drawn-out horns. The sort of thing you might expect with a fast-paced montage showing newspapers being printed on deadline or vital telegraph messages going out across the lines.)Here, the following conventions get invoked: i. the Heist / Master Criminal plot, ii. the Arent-as-Comedy-Routine plot, and iii. the Kinski-as-Grotesque plot. The question is: What "degree of execution" do the cast and crew manage in pulling them off?

|

| Heinz Drache, the series' second-string detective, is on the case. |

[BACK TO THE PROLOGUE]

After we get the unexplained Kinski appearance, and the credits, we cut to what feels like the other half of the prologue: A car slides to a stop in the snow at the foot of a phone box. The driver rushes into the box and phones his brother, breathlessly confessing that he knows the identity of someone called "The Snake". Before he can reveal the name, a mysterious man comes up behind him, pulls out a telescoping metal tube with trigger, and "shoots" the man with an unknown poison. After the man dies, the mystery man pulls out the head of a snake and sinks the fangs into the dead man's neck. Who is this mysterious Snake? What connection does he have to Old Lady Mulford (Agnes Windeck) and the business she runs importing and exporting wild animals? Will her insistence on employing paroled ex-cons open her fortune up to the clutches of The Snake? And how does slinking, smirking, big-eyed Klaus Kinski figure into the mix?

[VOHRER'S NOTHING IF NOT STYLE IN SPADES]

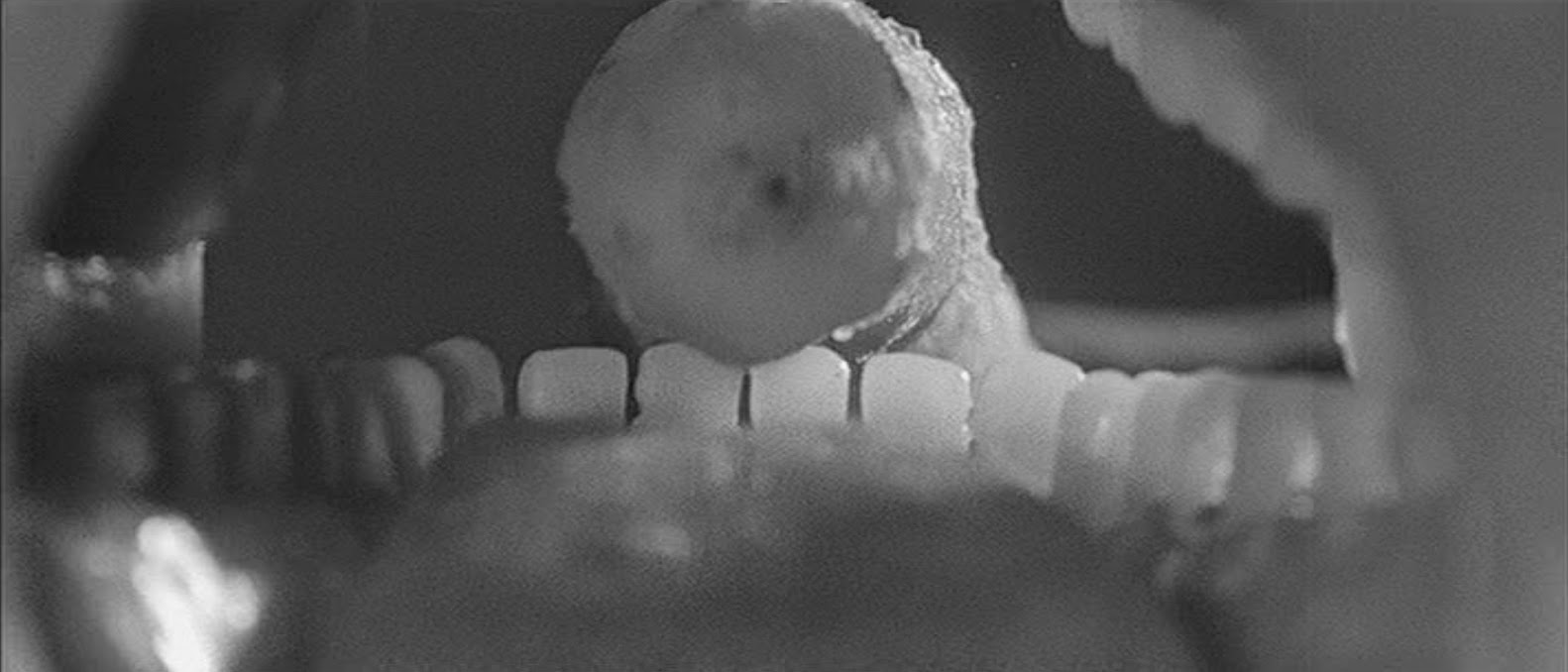

This double-sided prologue helps cement the film's style (flourishes that are familiar to anyone who's been watching Vohrer's output). In quick succession we get more of these flashes of style, including one of V.'s patented "inside the mouth shots," here gifted to Siegfried Schürenberg's character:

|

| Vohrer includes a similar shot in 1961's DEAD EYES OF LONDON, where we watch a man using a water-pick on his teeth, but from the inside. |

V.'s eye extends to set dressing and camera setups. When the owner of a gym calls his gangland boss to report that Scotland Yard (in the guise of genre second-fiddle Heinz Drache) has been snooping around, suddenly visual jokes abound. We see the ringing phone in a hazy bar, and watch as the bartender carries the phone over to the boss. In the foreground of the shot, you see the stuffed head of an animal; resting in the animal's right nostril is a lit cigarette with an enormous ash hanging off its end. When the phone is ringing, V. flanks the phone with the details of other people at the bar—body parts of two customers, one with his elbow resting on the bar, the other whose hand is flicking open a knife into the frame:

There's also plenty more style concentrated around Kinski. First, his red herring status is confirmed by V.'s visuals, wherein we watch Kinski lovingly handle a snake while upside-down in bed:

[WHERE DER ZINKER'S FORMULA FALTERS]

Almost without exception, one or more of the subplots in a given Krimi end up going nowhere. Feeling like stranded, ill-fitting chunks of plot. Here it's a jewelry store robbery that a rival gang of The Snake's pulls off so they can set up a "drop" with him. (This is the gang that shows up in the "smoking stuffed animal" bar scene capped above.)

It has a nice gimmick—two of the gang members, a father and son, stage a fake heart attack outside the jewelry store to distract the cops during the heist. But the time spent on the scene—as well as the follow-on scenes that show Drache interrogating members of the gang, and the gang getting themselves gunned down when the meet with The Snake goes bad—feel like padding. Vohrer takes little stylistic license in their presentation, and it feels a little like the police portions of Bava's BLOOD AND BLACK LACE: the case of a director who doesn't know what to do with the expository scenes required by the script.

(Speaking of which, Drache gets one of the most perfunctory detective roles in the whole series. His character could easily be removed from the movie without altering the material all that much.)Likewise with the intrigue in Old Lady Mulford's mansion concerning Jan Hendrik's ex-convict character. There's too much time spent setting up his murder (which is, admittedly, part of that spectacular sequence above), having him prowl around the house in the dark, looking for the safe he's meant to crack. I.e., I don't think it's an accident that the ill-fitting sections of plot that I mention here also contain sequences that I singled out for their standout style. This is almost always the give-and-take of the Krimi—how much style does it take to make up for how much of a plodding or unwieldy plot (or: cringe-inducing humor)? The answer to this question is usually also the answer to another: Is this Krimi worth a watch?

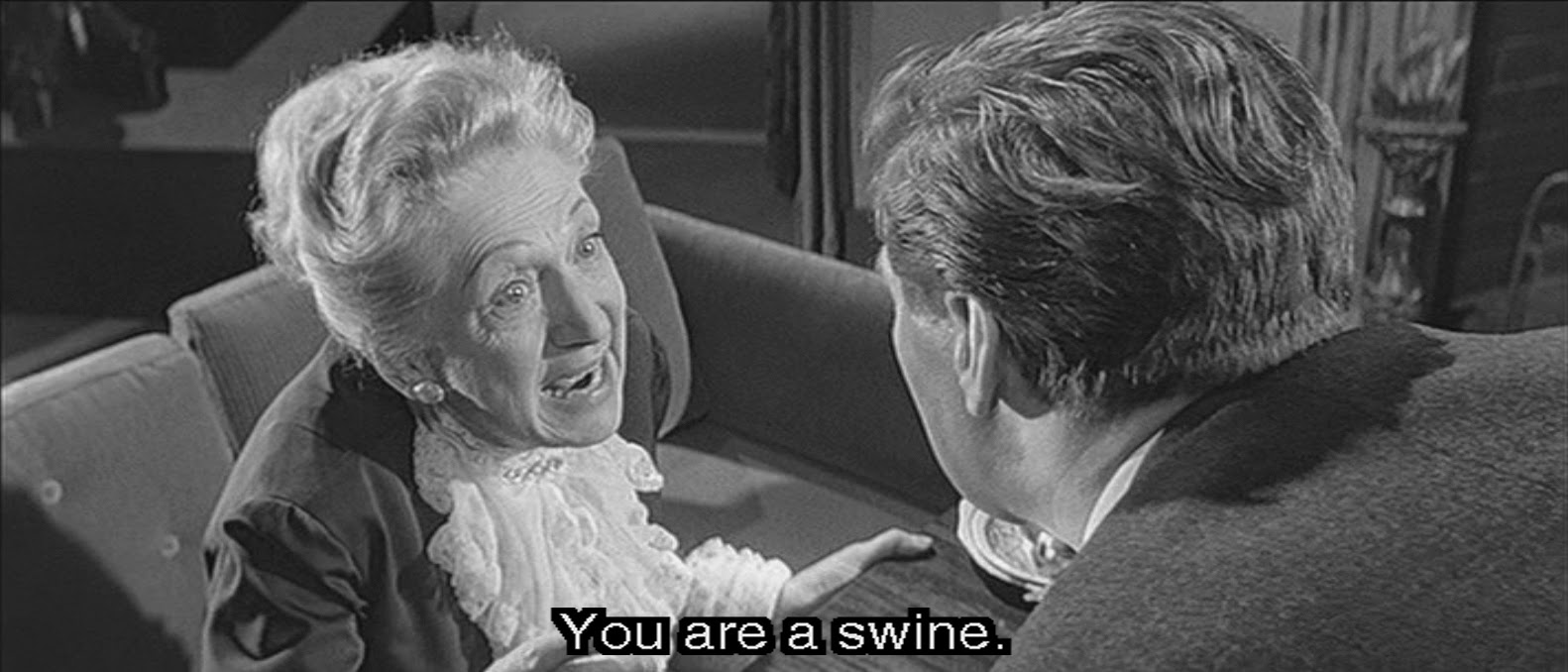

Her introduction is itself a visual gag: By the framing and use of soundtack, we're led to believe that she's conducting an orchestra. As the camera pulls back, we realize that she's "conducting" to a classical recording that's playing in the sitting room of her country estate. Her long-suffering audience (family member, employee, and high-society friend) are about as interested in the performance as you might expect.

|

| Windeck played this slightly dotty, usually rich Old Dame more than once—in 1968's THE MONSTER OF BLACKWOOD CASTLE (which also, coincidentally, featured prominent use of poisonous snakes), as well as 1966's THE HUNCHBACK OF SOHO. Here, as in HUNCHBACK, she is harboring a secret that is only revealed in the climax, and causes us to re-evaluate the condescending attitude that her old-fashioned-ness invites from us as the audience. |

|

| Her oh-so-attentive audience: manager of Windeck's menagerie of animals, Günter Pfitzmann; her niece (and Pfitzmann's onscreen girlfriend) Barbara Rütting. Rütting here plays a character very similar to the one she plays in the superior PHANTOM OF SOHO: In both she is an amateur sleuth/mystery writer whose investigation of the murders is tied up with the writing of her latest book. Making her the proto-Giallo killer in SOHO, with a cruel trauma driving her from her past, is imo a much more interesting version of the character, which gets mostly short-shrift here. |

The twist that resides in Windeck's character almost saves it, as the Old Dame turns the tables on the murderer (who thinks she's an imbecile). With the help of Drache, she spikes the killer's drink with a paralyzing drug and forces him to confess both that he is The Snake, and that he blackmailed her husband into an early grave in order to take over her company.

This nastiness leads into Kinski making his last appearance, bursting through a window in the ceiling with machine gun in hand (turns out The Snake had been exploiting his character's mental problems in order to get him to do some of the dirty work).

And ... maybe if the movie had ended on those two nasty bursts of violence, it would rank more highly in the canon. Unfortunately we get a variation on the fourth-wall-breaking "Ende gag" that would too often let the air out of the stories that had gone before. Here, Windeck's Lady Mulford addresses the portrait of her dead husband, asking his forgiveness for the way she treated his killer—and? The portrait answers her, assuring her that her feint was something worthy of Edgar Wallace. :\

|

| The humor seems esp. ill-judged, as Windeck appears visibly shaken by what she's just done. |

Leonard Jacobs

December, 2014

[SHOW NOTES]

VERSION WATCHED: The version included in Vol. 3 of the German Edgar Wallace Box Sets | LANGUAGE: German with English subs | DIRECTOR: Alfred Vohrer | WRITER(S): Edgar Wallace, Harald G. Petersson | MUSIC: Peter Thomas | CINEMATOGRAPHER: Karl Löb | CAST: Heinz Drache (Inspector Bill Elford); Barbara Rütting (Beryl Stedman); Günter Pfitzmann (Frankie Sutton); Jan Hendriks (Thomas Leslie); Inge Langen (Millie Trent); Agnes Windeck (Mrs. Nancy Mulford); Wolfgang Wahl (Sergeant Lomm); Siegfried Wischnewski (Der Lord); Siegfried Schürenberg (Sir Geoffrey Fielding); Albert Bessler (Butler); Heinz Spitzner (Dr. Green); Stanislav Ledinek (Der Champ); Winfried Groth (Jimmy); Eddi Arent (Josua "Jos" Harras); Klaus Kinski (Krishna)

No comments:

Post a Comment