[Note:

This is the seventh post in a continuing series discussing and analyzing

our favorite Krimis and Gialli (some of the reviews started as rough

drafts on my Letterboxd account). As with every post on this site, SPOILERS SHOULD BE EXPECTED.]

My Krimi Rating: ★★★★☆

Subcategory (if any):

i. Heist / Master Criminal Krimi

ii. Ingénue in Distress Krimi

iii. Proto-Giallo Krimi

iv. Arent-as-Comedy-Routine

Who Portrays the Detective (amateur or official):

Eddi Arent (official); Joachim Fuchsberger (amateur)

Who's the Ingénue:

Karin Dor

In My Krimi Top 20 (Y/N): Yes (Letterboxd link)

There are some of these Edgar Wallace/Bryan Edgar Wallace adaptations that seem positively crammed with crossed plot lines and competing genres. They don’t qualify so much as hybrids—like a Gothic Giallo, or a Giallo Poliziotteschi—but as potboilers painfully overflowing their pots. Of the ~30 Krimis I’ve seen so far, the best example that comes to mind is one I’ve discussed recently with a reader of the blog here, THE MAD EXECUTIONERS (see the comments for this post). And, according to this write-up on the movie over at Giallo Fever, it appears that this feeling of an overstuffed, overstacked, overheated piling on of disparate plot devices isn’t accidental when it comes to that adaptation, as it’s maybe not the adaptation of one Wallace story, but two.

It’s a risk that all of these Krimis seem to run, one in which you can imagine the films’ production companies trying to find new and better twists to keep audiences of the long-running series interested in (if not exactly comprehending) every, next, wtf twist. If two or three twists are good box office, their thinking might’ve been, then why not five, or 10, or 20?

Who Portrays the Detective (amateur or official):

Eddi Arent (official); Joachim Fuchsberger (amateur)

Who's the Ingénue:

Karin Dor

In My Krimi Top 20 (Y/N): Yes (Letterboxd link)

There are some of these Edgar Wallace/Bryan Edgar Wallace adaptations that seem positively crammed with crossed plot lines and competing genres. They don’t qualify so much as hybrids—like a Gothic Giallo, or a Giallo Poliziotteschi—but as potboilers painfully overflowing their pots. Of the ~30 Krimis I’ve seen so far, the best example that comes to mind is one I’ve discussed recently with a reader of the blog here, THE MAD EXECUTIONERS (see the comments for this post). And, according to this write-up on the movie over at Giallo Fever, it appears that this feeling of an overstuffed, overstacked, overheated piling on of disparate plot devices isn’t accidental when it comes to that adaptation, as it’s maybe not the adaptation of one Wallace story, but two.

It’s a risk that all of these Krimis seem to run, one in which you can imagine the films’ production companies trying to find new and better twists to keep audiences of the long-running series interested in (if not exactly comprehending) every, next, wtf twist. If two or three twists are good box office, their thinking might’ve been, then why not five, or 10, or 20?

If Gothic-flavored inheritance schemes sell tickets, why not pile other popular ideas on top—how about a recently released master criminal who blackmails the socially prominent Lord of that Gothic castle?

And a meticulously rehearsed and planned bank heist that involves diverting and hijacking trains?

|

| Joachim Fuchsberger, in what could just as easily be an outtake from DER HEXER. |

|

| The Highlow Club, where a little too much of the plot goes to die. |

Etc.

Letterboxd user laird touches on this in his review, the very same review that, just about seven months ago, set me off on my "Krimi Quest" for the year:

"On the violence side of things, there's a black leather glove wearing psychopath running around murdering women with a straight razor. This is mostly background to another plot thread about blackmail, a dead wife, a criminal investigation, and a gang leader's plan to rob a train. It's needlessly convoluted...you really start to see why these are considered forefather to the giallo films of the 70s."

(Another interesting factoid from him: "The brief scene of nudity apparently earned this movie an 18+ rating in

Germany where it became the first of the Rialto productions to fail at

the box office.")

All of the plot lines mentioned

above figure variously ROOM 13. But unlike the frustrating lopsidedness of THE MAD EXECUTIONERS, I found that R13 (mostly) wove its plot threads into a weirdly compelling cloth. It’s still not an entirely

successful film, but what succeeds of it is as compelling as anything

else in the genre. And helps make me forget how regrettable the other plot threads (not to mention comedy routines) tend to be.

Part of this is because, again, it offers a glimpse of the way that proto-Giallo influences were developing outside of Italy (also proto-psychosexual conventions). Part is because it takes the strange narrative tact of “burying its lead,” submerging the most compelling sections of the film beneath the tediously staged heist. This most compelling thread in the film is the character and arc of Denise Marney, played by the genre-defining Karin Dor (with her then-husband Harald Reinl directing). I.e., when Dor is onscreen as the embodiment of her strange throughline, this is top-tier stuff.

Part of this is because, again, it offers a glimpse of the way that proto-Giallo influences were developing outside of Italy (also proto-psychosexual conventions). Part is because it takes the strange narrative tact of “burying its lead,” submerging the most compelling sections of the film beneath the tediously staged heist. This most compelling thread in the film is the character and arc of Denise Marney, played by the genre-defining Karin Dor (with her then-husband Harald Reinl directing). I.e., when Dor is onscreen as the embodiment of her strange throughline, this is top-tier stuff.

|

| Like mother like trauma? |

[THE MANY LIVES OF KARIN DOR]

|

| Behind the screen, the disembodied hand of the killer waits. |

|

| She "takes her bow," backing her way behind the uprights. |

Fuchsberger is stuck outside the club with no way to enter, and is about to leave when Dor's screams sound from inside. He breaks down the front door and finds her fleeing down the stairs; he randomly guns down one of the blackmailer's gang and escapes with Dor as she desperately tells him what she saw after finding the razor: Another murder.

Tbh, I could do without this whole section of the movie; it feels like the equivalent of overly dry, overly complicated exposition, in a movie that otherwise lives and dies by the strengths of its deeply weird nightmare-stuff. No doubt the multi-stage heist was meant to evoke the kind of tense, breathless bravura of the extended set piece in a movie like RIFIFI. Instead it feels needlessly padded, needlessly drawn-out. There’s no tension or suspense about how it will turn out, because, quite frankly, whatever happens is of no consequence to the dramatic power (or pulped-out interest) of the movie.

Do we really care, as viewers, whether the blackmailer's gang will pull off the heist? Do any of the heist’s details hold within them the weird frissoning moments that mark the best Krimis? Does the heist and its outcome have anything, anything, to do with the Giallo-razor murders that keep cropping up in the movie's narratives like chunks of bad dream? No. No. And no.

Even intercutting the unfolding heist with Fuchsberger and Arent trying to rescue Dor from the club doesn't help things.

What does help—and nearly rescues the movie from its slough of mediocrity—is the final however-minutes devoted to unveiling the real Denise (Dor). Devoted to removing what has so far been obscured by her face, in her brain. The real mystery wadded up in the 20-year-old tragedy that her father repeatedly refuses to speak on. The true reason, in fact, that *anything* compelling exists within the story:

[ART AS TRIGGER]

The use of art objects to trigger

pathology in the viewer has a long literary history. For the Krimi/Giallo tradition, it maybe starts with the 1949

psycho-noir THE SCREAMING MIMI, written by Fredric Brown. This story was "unofficially" adapted as Argento’s BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL

PLUMAGE.

In the book, the titular Screaming Mimi is a statue

depicting a traumatic, repressed moment in statuesque dancer

Yolanda’s past life (her attack, on a beach, by an escaped mental

patient). When she sees the statue again, living a new, "cured" life in the Big Apple, the trauma still packed in the gray of her brain becomes just as traumatically unpacked, as she proceeds to re-enact her trauma by projecting it onto others, obsessively killing women throughout the city.

In BIRD, the Mimi statue has morphed into a Mimi painting, which triggers Monica Ranieri's (Eva Renzi's) regression to the day of her own attack (she is the Yolanda character here). Like in the book, she no longer identifies herself with the victim of the attack, but with the attacker. With his identity newly lodged in her brain, she stalks and kills women who remind her of her past victim-hood; she seeks to obliterate her role as victim by obliterating as many additional women as she can.

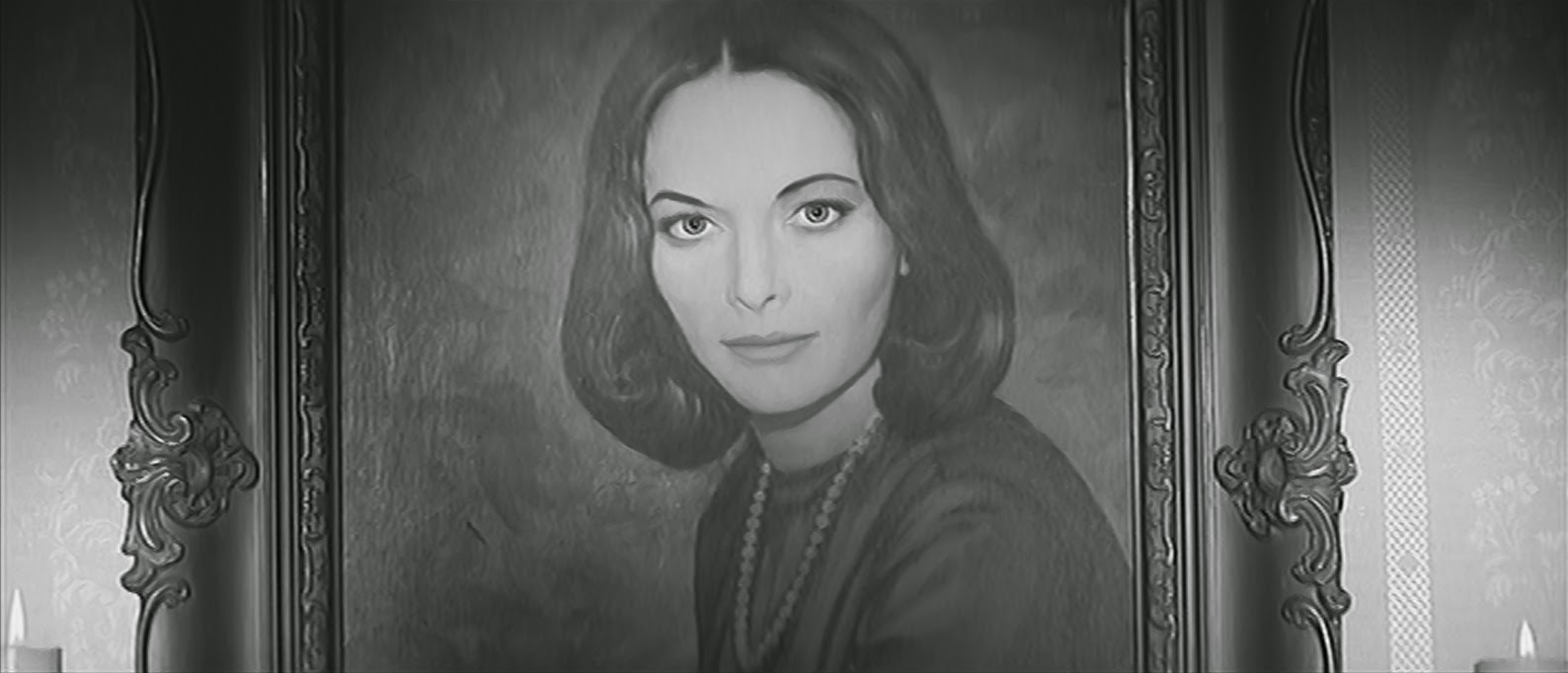

In R13, Dor is the sufferer of this fate, not because of an attack on her life, but because she witnessed her mother’s suicide at age 5 (her mother, again, who is also her physical double according to the portrait that hangs in her bedroom). This "final reveal" is set into motion by F., who stages the last few experiences Dor's character has in such a way so as to recreate the conditions of her mother's suicide:

In BIRD, the Mimi statue has morphed into a Mimi painting, which triggers Monica Ranieri's (Eva Renzi's) regression to the day of her own attack (she is the Yolanda character here). Like in the book, she no longer identifies herself with the victim of the attack, but with the attacker. With his identity newly lodged in her brain, she stalks and kills women who remind her of her past victim-hood; she seeks to obliterate her role as victim by obliterating as many additional women as she can.

In R13, Dor is the sufferer of this fate, not because of an attack on her life, but because she witnessed her mother’s suicide at age 5 (her mother, again, who is also her physical double according to the portrait that hangs in her bedroom). This "final reveal" is set into motion by F., who stages the last few experiences Dor's character has in such a way so as to recreate the conditions of her mother's suicide:

|

| What she does with her face in these scenes reminds me an awful lot of Nieves Navarro's facial expressions, during her drug-induced nightmare vision at the beginning of DEATH WALKS AT MIDNIGHT. |

Exactly like Brown's Yolanda. And Argento's Monica.

(At first I took that last line from F.'s speech to mean that Dor's mother was possibly a proto-proto-Giallo

killer, who herself

murdered an unknown number of women 20 years earlier, before turning

the razor on herself. When I rewatched the scene to transcribe the

speech, though, I decided that he was referring only to her suicide.)

Fuchsberger’s resigned, pensive,

world-weary retreat at the end of the film—high contrast to his

introduction, dallying in bed with a nameless woman who is clearly meant to represent one of his

empty “flings”—suggests both that he had genuinely developed

feelings for Dor’s character, and that his devil-may-care/crack-adventurer/ace-detective worldview has been irreparably crippled. And crippled in a way that he has no ability or special skill to fight. Though he

has “won” the day by solving the case (the case that bumbling

Scotland Yard couldn’t manage on its own), its solution is also his defeat. The mannequin trigger that he

left in Dor’s room succeeded in triggering her final stage of psychosis. But its triggering also spun out of his control: essentially, he *caused* Dor's death by suicide in order to solve the case.

The final sequence with his character shows F. channeling all this despair in pretty impressive and understated ways. His face shows us that he knows he was complicit in her death. His face shows us that he has finally met a moment in life that his vaunted skills and youth-charisma cannot match. He is no longer up to the task. All he can do, his face seems to say, is to give up. Resign himself to it. Shrink before it. Get in his car and drive away from it.

The final sequence with his character shows F. channeling all this despair in pretty impressive and understated ways. His face shows us that he knows he was complicit in her death. His face shows us that he has finally met a moment in life that his vaunted skills and youth-charisma cannot match. He is no longer up to the task. All he can do, his face seems to say, is to give up. Resign himself to it. Shrink before it. Get in his car and drive away from it.

He starts the sequence, disgusted by Arent's shallow, stupid prattling about his "love" for his mannequin Emily (after his lengthy speech explaining Dor's motives, he does not utter another word in the film):

Leonard Jacobs

September, 2014

VERSION WATCHED: The German DVD release offered in Vol. 4 of the Edgar Wallace Box Sets. | LANGUAGE: German soundtrack with English subs; almost always the way to go if possible. | DIRECTOR: Harald Reinl | WRITER(S): Edgar Wallace, Will Tremper | MUSIC: Peter Thomas | CINEMATOGRAPHER: Ernst W. Kalinke | CAST: Joachim

Fuchsberger (Johnny Gray); Karin Dor (Denise Marney/Dead Mother Marney); Richard Häussler (Joe Legge); Walter Rilla (Sir Marney); Siegfried Schürenberg (Sir John); Kai Fischer (Pia Pasani); Benno Hoffmann (Blackstone-Edward); Bruno W. Pantel (Sergeant Horse); Kurd Pieritz (Inspector Terrence); Erik Radolf (Ambrose); Eddi Arent (Dr. Higgins); Hans Clarin (Mr. Igle)

[SHOW NOTES]

No comments:

Post a Comment