[Note:

This is the twenty-first post in a continuing series discussing and analyzing

all the Krimis and Gialli I've seen. As with every post on this site, SPOILERS SHOULD BE EXPECTED.]

My Krimi Rating: ★★★★★

Subcategory (if any):

i. Heist / Master Criminal Krimi

ii. Ingénue in Distress Krimi

iii. Inheritance Scheme Krimi

iv. Proto-Giallo Krimi

v. Arent-as-Comedy-Routine

Who Portrays the Detective (amateur or official):

Joachim Fuchsberger (official)

Who's the Ingénue:

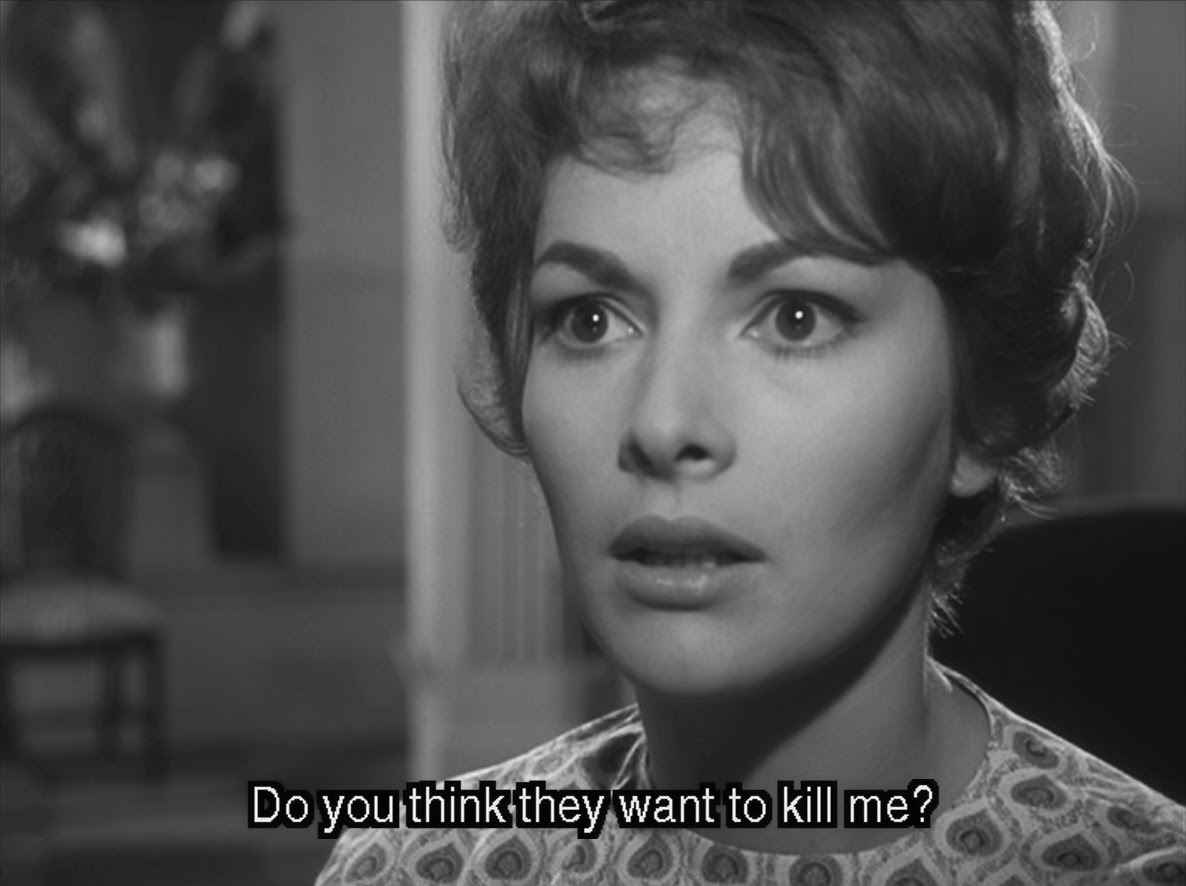

Karin Dor

In My Krimi Top 20 (Y/N): Yes (Letterboxd link)

[THE PRE-INTRODUCTION]

Though I'd been marginally aware of a genre called the Krimi—and its potential influence on the Italian Giallo cycle that flourished after it had mostly died—it took a list on Letterboxd to get me serious about tracking down the films. Using Holger Haase's Rialto list as my starting point, I watched my first “official” Krimi back in February. Since then, I've upped my total to 43, and have compiled a Master List that tells me I've got at least 40 more to go. This 2014 “Krimi Quest” spawned not only a series of Letterboxd reviews, but this blog. I wanted a space where anything and everything related to the Krimi and Giallo could be compiled, analyzed, enjoyed, accessed. I've greatly enjoyed the comments, feedback, and info that's been sent my way since August—here's hoping 2015 proves even more productive (and collaborative).

With the time I have remaining before New Years, I'm going to (hopefully) finish up a couple more items: 1. The first chronology page for the Giallo Master List (listing Gialli and Proto-Gialli from 1934-1969), 2. a return to the “Sleaze-Art-Sleaze” Giallo reviews, and 3. some thoughts on those Krimis that are my most (and least) favorite, starting with this review. My perspective may change (the more Krimis I watch, the more I re-evaluate my ratings for the ones I've seen), but this will hopefully be a reference point, if nothing else, re: where my Krimi mind was at the end of December 2014. Thanks to all who took the time to read, comment, post links, etc.—I hope you'll stick with the site as it expands into 2015. Cheers!

Though there are other Krimis that feel more modern, other Krimis that are more transgressive, more directly a precursor to the psychosexual/trauma model that would later become the dominant shape taken by the Italian Giallo, there is no Krimi I adore more than 1960's THE TERRIBLE PEOPLE. It is a movie that does its best to resist this adoration. On a first watch, its plot is convoluted to the point of incoherence, with a cast of obliquely interrelated characters that really can't be kept track of (at least, not very easily). It is also, on its surface, one of the most “dated” Krimis—from Karin Dor's ingénue-in-distress, lacking as she does almost all agency (though her staunch refusal to either be forced into marriage or to betray Fuchsberger's character—even under threat of some Fulci-level eye violence—should be noted), to the potentially old-fashioned Agathe Christie “Drawing Room Mystery”-type inheritance plot, it seems like its presentation of premise will be, no matter what else, quaint. Even, as some call the genre, a bit too “Scooby Doo”.

But:

Watch it more than once, and these apparent marks against it recede into the background, reveal themselves to be a reductive misunderstanding of a Krimi that is, perhaps more than any other, structured like something out of a dream. A story deformed so that it pushes past its a-b-c mystery plot, past the frame of its black-and-white 60s-vintage, to follow associative and unexplained rules that look like dream logic. AND THEN THERE WERE NONE by way of a MAN WHO WAS THURSDAY nightmare.

G.K. Chesterton's THURSDAY is a good touchstone for understanding the Krimi. It is a highly stylized, action-packed, detective story—a globe-trotting chase between undercover Scotland Yard detectives and crooked-faced anarchists—that is *also* a metaphysical mind melt. More than Father Brown, it grapples head-on, head-back, and howling with the notion of a “terrible-good” Christian deity who maybe, just maybe, is more nightmare than anything else. Considering Chesterton's own religious and philosophical leanings—he did, after all, write a book called ORTHODOXY—it feels esp. problematic and challenging. There is little comforting about a deity who, when first glimpsed, is described like this:

“[Detective] Syme had never thought of asking whether the monstrous man who almost filled and broke the balcony was the great President of whom the others stood in awe. He knew it was so, with an unaccountable but instantaneous certainty. Syme, indeed, was one of those men who are open to all the more nameless psychological influences in a degree a little dangerous to mental health. Utterly devoid of fear in physical dangers, he was a great deal too sensitive to the smell of spiritual evil. Twice already that night little unmeaning things had peeped out at him almost pruriently, and given him a sense of drawing nearer and nearer to the head-quarters of hell. And this sense became overpowering as he drew nearer to the great President.It, like THE TERRIBLE PEOPLE, is grotesque in the best and most fascinating ways, grotesque because it is “strange, fantastic, ugly, incongruous, unpleasant, or disgusting,” full of “weird shapes and distorted forms” that “simultaneously invoke in an audience a feeling of uncomfortable bizarreness as well as sympathetic pity.”

“The form it took was a childish and yet hateful fancy. As he walked across the inner room towards the balcony, the large face of [President] Sunday grew larger and larger; and Syme was gripped with a fear that when he was quite close the face would be too big to be possible, and that he would scream aloud. He remembered that as a child he would not look at the mask of Memnon in the British Museum, because it was a face, and so large.”

Like Philip K. Dick's VALIS (with its heartbreakingly weird narrative), or Patrick McGoohan's “bitter hero raging against a nightmare system of universe that is both malevolent and hopelessly stacked against him”-spy opus THE PRISONER, or the unfixable oblivion that overwhelms David Foster Wallace's story of the same name, what I find most frightening, most touching, most indelible about the Krimi is not when it's camp (and thus can be easily or ironically laughed at), not when it's bogged down in detective mystery mechanics, not when it's lifelessly repeating itself, but when it's impossible not to acknowledge the grotesque flicker of its film.

The plot seems straightforward enough: Clay Shelton, a master criminal notorious for the shadowy network of operatives under his control, is foiled during a bank robbery. He is foiled by Chefinspektor “Blacky” Long (Joachim Fuchsberger), but also by a handful of bystanders in the bank who seem to accidentally gum up his attempt to shoot his way free. In his cell, on the eve of his execution, he gathers all those he deems responsible for his death sentence and vows that his “Gallow's Hand” will reach beyond the grave and murder them, one by one.

(There’s an old MURDER AT MIDNIGHT radio episode called “No Grave Can Hold Me” that uses a very similar plot, an executed man who appears to return from the grave to murder all those responsible for his execution. In this case, the man, a professional mesmerist, manages to hypnotize his death-row guard into disguising himself as the executed man and carrying out the murders. Both this story and Wallace's contain a key scene where the executed man's grave is opened, in order to confirm whether or not he's really dead.)

From that point on, the movie is a series of murder attempts on those that Shelton has marked for death, each scene somehow prominently featuring the clutching death hand itself. Even when the murder attempts fail—as in the first attempt on Long’s life—the attackers make sure to flash the hand sign even as they die. Being an Edgar Wallace story, there are also subplots involving banking irregularities, blackmail schemes, a stolen inheritance, and an unknowing heir. These specifics are less important, though, than in some of the other films, and what sticks with me are the nightmare details.

|

| Back projection as mood. |

Shelton's reach from beyond the grave, his “Gallow's Hand”: We get this both as the key detail of his ghostly appearances (a phantom haunting each crime scene) and as a clutching, inexplicable sign thrown up by each of his operatives when they try to kill someone on his list. The first murder attempt, on unbelieving Inspector Long, begins when his tire blows. He wrestles the car to a stop and gets out, only to discover that someone has put a nail-studded board in the road. While examining this, someone shoots the end off his pipe (instead of a hole in his head), and Long takes cover to return fire.

|

| An unexplained puff of smoke seems to be the first glimpse we get of Long's would-be sniper. |

[THE SECOND NIGHTMARE: A CRUEL PICTURE]

There are a handful of exceedingly cruel Krimis. Cruelty that feels like it puts the characters at a kind of metaphysical disadvantage—that suggests there are forces in the universe that simply cannot be prevailed upon. In the face of them, your only possible outcome is cruel and unusual death. (When I write up Vohrer's DEAD EYES OF LONDON I'll come back to this theme, spending some time on the elevator murder for one [where a man's hands are both smashed by the killer's heel and burned with cigarettes to get him to fall].)

It reminds me of the quote that Maitland McDonagh uses to open her introduction of BROKEN MIRRORS/BROKEN MINDS. She uses the quote to get at the “dislocation” found in Argento's work. But it applies here just the same:

“A man named Flitcraft had left his real-estate-office, in Tacoma, to go to luncheon one day and had never returned ... Here's what happened to him. Going to lunch he passed an office-building that was being put up—just the skeleton. A beam or something fell eight or ten stories down and smacked the sidewalk alongside him. It brushed pretty close to him, but didn't touch him, though a piece of the sidewalk was chipped off and flew up and hit his cheek. It only took a piece of skin off, but he still had the scar when I saw him. He rubbed it with his finger—well, affectionately—when he told me about it. He was scared stiff of course, he said, but he was more shocked than really frightened. He felt like somebody had taken the lid off life and let him look at the works. Flitcraft had been a good citizen and a good husband and father, not by any outer compulsion, but simply because he was a man most comfortable in step with his surroundings. He had been raised that way. The people he knew were like that. The life he knew was a clean orderly sane responsible affair. Now a falling beam had shown him that life was fundamentally none of these things. He, the good citizen-husband-father, could be wiped out between office and restaurant by the accident of a falling beam. He knew then that men died at haphazard like that, and lived only while blind chance spared them. It was not, primarily, the injustice of it that disturbed him: he accepted that after the first shock. What disturbed him was the discovery that in sensibly ordering his affairs he had got out of step, and not in step, with life.”This sense of dislocation links TERRIBLE PEOPLE to the world of the proto-Giallo. Because, unlike the “traditional” Krimi that reinforces “[f]aith in the dependability of the social order which the detective figure … embodies” the judge's murder is just one of several that suggests something deeply broken in the social order of Inspector Long's world. After all, the judge who is murdered in his own home by an impossibly falling staircase was innocent, at least as far as Shelton went. Shelton's conviction was a just one—he was guilty of the bank robbery and many worse crimes that he'd masterminded before the start of the film. In a just, dependable world, the judge would have lived. Even with THE TERRIBLE PEOPLE's seemingly “happy ending”—the characters played by Fuchsberger and Dor are destined to marry, a last shot showing them able to laugh in the face of what they've been through—the film's actual events hew much more closely to a Giallo mystery whose resolution “fails fully to restore either the viewers' or the characters' faith in a coherent moral or perceptual universe.” (Do we really believe the smile on their faces ending the film? Or are we more likely to think of the downbeat, suicidal, spiritually hopeless ending of another Reinl masterwork, ROOM 13, where Fuchsberger's ingenuity as detective does nothing but drive Dor to suicide.)

—THE MALTESE FALCON

The next excessive, cruel murder is that of Shelton's hangman. He comes to Long's house, frantic and drunk. Having heard of the death of those on Shelton's list, he fears he'll be next. Long puts him in an upstairs bedroom and posts a guard outside his door. And yet … not only is he murdered, but in a surrealistically violent way—he is hung while he's still lying on the floor. The killer somehow scales the outside of the house, enters the hangman's second-story bedroom, and places a noose around his neck. Before the hangman can get free, the killer (apparently) jumps out of the second-story window and uses his own body weight (attached to the noose) to drag the hangman across the room, against the window frame, and snap his neck. (It sounds even weirder the more I try to describe it.)

For one of the members of Shelton's gang, there's being tied to a chair and plunged into an open shaft several stories tall (by other members of Shelton's gang no less, while Dor's character is made to watch):

[NIGHTMARE #3: SOMETIMES THE MOVIE IS JUST INSANE]

Nora (Karin Dor) plays Mrs. Revelstoke's (Elisabeth Flickenschildt's) secretary. Throughout the movie she is hounded by Flickenschildt's lawyer, Mr. Henry (Ulrich Beiger, playing a sleazy, distrustful attorney not unlike the one he played in THE RED CIRCLE). At one point, Henry corners Nora in her hotel room and attempts to force her to marry him. When a police officer, drawn by Nora's shouts, bursts into the room and demands to know what's going on, Henry comes suddenly unhinged:

The insanity seems to orbit around the two female leads—Flickenschildt and Dor. In a genre full of ace casting, I really can't overstate how important their presence is to the gravitas, the frisson and success of a given Krimi. Whether it's Flickenschildt as the wheelchair-bound, block-toothed club owner Joanna Filiati in the proto-TENEBRAE Krimi PHANTOM OF SOHO, or Karin Dor as the nuanced, world-wearied victim of her family's ghastly attacks in THE SINISTER MONK, these two actresses always elevate the Krimis they exist within.

The film lives and dies by its status as a pulpy weird love letter to the genre, a genre that is, at its best, as much associative nightmare as solvable mystery. And, as Inspector Long says: “Love letters are always menacing.”

Nora (Karin Dor) plays Mrs. Revelstoke's (Elisabeth Flickenschildt's) secretary. Throughout the movie she is hounded by Flickenschildt's lawyer, Mr. Henry (Ulrich Beiger, playing a sleazy, distrustful attorney not unlike the one he played in THE RED CIRCLE). At one point, Henry corners Nora in her hotel room and attempts to force her to marry him. When a police officer, drawn by Nora's shouts, bursts into the room and demands to know what's going on, Henry comes suddenly unhinged:

|

| Dor's character is the one that the nightmare gets written upon—Flickenschildt's character is the one doing the writing. |

Leonard Jacobs

December, 2014

[SHOW NOTES]

VERSION WATCHED: The German DVD release offered in Vol. 1 of the Edgar Wallace Box Sets | LANGUAGE: German soundtrack with English subs, though it surprisingly has problems. About two-thirds of the way through, the English translation suddenly reads as though translated by a machine. It's an unfortunate blemish on an otherwise solid presentation of the film. | DIRECTOR: Harald Reinl | WRITER(S): Edgar Wallace, J. Joachim Bartsch, Wolfgang Schnitzler | MUSIC: Heinz Funk | CINEMATOGRAPHER: Albert Benitz | CAST: Joachim Fuchsberger (Chefinspektor Long); Karin Dor (Nora Sanders); Fritz Rasp (Lord Godley Long); Dieter Eppler (Mr. Crayley); Ulrich Beiger (Mr. Henry); Karin Kernke (Alice Cravel); Ernst Fritz Fürbringer (Sir Archibald); Eddi Arent (Antony Edwards); Karl-Georg Saebisch (Bankier Monkford / Lehrer Monkford); Alf Marholm (Richard Cravel); Elisabeth Flickenschildt (Mrs. Revelstoke); Otto Collin (Clay Shelton)

Excellent write-up. This is one krimi that I definitely look forward to revisiting.

ReplyDeleteThanks. I realized after I posted it that I forgot to include the caps about how there are other Shelton "ringers" in the cast, including one that's used to transition from Arent spotting the dead man in the mist to the ringer himself. Maybe the review's already long enough though ;)

DeleteIt may seem a little crude to ponder on this seemingly trivial aspect so much, but for me, those are the moments in which these films - sometimes - "break" the fourth wall, because in this genre, violence (as everything else) is not normally realistic and/or of the kind that makes you cringe but rather staged and admittedly artificial "excitement" (as I wrote above). Reinl's violence often goes beyond that point (as opposed to Vohrer's, which is either maturely self-conscious or outrageously ironical) and perturbs the fairy-tale impression of these films. While Vohrer (like Paul Verhoeven) consciously and gleefully admits that the audience craves sex and violence and lucidly and unabashedly yields to this presumption (and thoroughly enjoys himself by doing so), Reinl, generally much more conservative and impersonal, seems to wade in it obliviously, as if he sometimes missed the line between the spectacular and excess. He said of himself that he was always trying to be as spectacular as possible, but then, he also condemned the increase of sex and violence in films (he said the former in 1967 and the latter in 1984, mind you). If I had had the chance of interviewing Alfred Vohrer on this topic, I'm sure he would've given me a sly smile or chuckle, indicating that he knows exactly what I'm getting at, but preferring to remain silent. As for Reinl, I'm not so sure. Which makes his sadism all the more interesting, because it penetrates the cleanliness he otherwise maintained so well. You could make a case of ROOM 13 (one of the most interesting Krimis for sure) deconstructing my theory, but it should be kept in mind that this film was (astonishingly!) written by Will Tremper, himself more of an intellectual filmmaker and journalist, who obviously strived to give the film a level of realism and psychological depth which he must've found missing from the earlier Wallace films. Watching Tremper's films (I recommend THE ENDLESS NIGHT, it's a masterpiece and available with English subtitles), it's not hard to link the standout elements of ROOM 13 to Tremper's work, and Reinl, being a true professional (just as Vohrer, who would hardly object to the screenplays he was handed) just filmed what was written. Sadly, ROOM 13 was a flop (perhaps, in part, due to commercially damaging 18 rating - it was the first - and for years, the only - Wallace film to earn it) and this refreshing approach was not pursued until much later (THE MANN WITH THE GLASS EYE, perhaps) because in this case, it did blend surprisingly well with the Krimi's fairy-tale-ishness.

ReplyDelete(Since I'm German, I hope any errors in this comment will be forgiven.)

Wow, well-said! Many thanks for the in-depth and insightful comments. Your knowledge of the Krimi (and Reinl and Vohrer in particular) is enviable. I'll add THE ENDLESS NIGHT to my watchlist (thanks for putting it on my radar). My hope is that, before 2015 is out, I'll have been able to see the Reinl & Vohrer films I'm still missing (and will be able to write them up for the site). Really appreciate you taking the time to post.

DeleteYou're quite welcome. I'm happy to see some serious appreciation of these films outside of Germany. So far, I never had the feeling that anybody abroad ever took them seriously.

ReplyDeleteOnly I'm afraid that somehow, the first half of my comment got lost in transmission! Here it is again, complementing the second half above (but, perhaps, not quite enlightening as browsing your blog further, I realised how many Krimis you've already seen):

Being a life-long die-hard fan of the Krimis and having often mused about how the vast difference between Reinl's and Vohrer's approach to the genre could be fleshed out by looking more closely at the way they depict both the most persistent clichés of the genre, as well as the (indeed surprisingly drastic, by West German standards of the time) violence, I'm fascinated by the fact that before reading your review, I never quite realised how closely related THE TERRIBLE PEOPLE is to Reinl's later film for "rival" producer Artur Brauner, THE STRANGLER OF BLACKMOOR CASTLE. Not only does the film step into similarly otherworldly terrain in terms of structure (the plot being nothing more than brackets around individual scenes and episodes, hardly connected by more than flimsy sentences), but Reinl also reproduces the "eye torturing" sequence with the exact same actors (Dor and Dieter Eppler), this time making Eppler a criminal jeweller who wants to "polish" Dor's eyes "like diamonds" which, of course, makes for a particularly bizarre, and, at the same time, rather unsettling moment. I've always thought that while Alfred Vohrer (whom I've grown to admire more and more while rewatching his films over the years, he's certainly my favourite director as far as the Wallace films are concerned, a true master of pulp excess) was more excessive and "embracing" in terms of on-screen violence (but rather in the way filmmakers such as Paul Verhoeven or Donald Cammell embrace violence - and sex, for that matter), he was never nearly as sadistic and cold-blooded as Reinl, who seemed to relish violence beyond the point of mere "movie excitement" which is most impressively demonstrated by THE WHITE SPIDER (another "rival" production, also starring Dor and Fuchsberger, who had become Krimi's number one dream couple by then), where he restages the "hanging" scene from THE TERRIBLE PEOPLE with a wire noose in a rather nasty, unpleasant scene which seems to go on forever and ever. Having watched every Krimi I could get my hands on as a teenager, I was quite surprised (and somewhat shocked), when I finally got hold of these "rival" productions in which Reinl apparently operated at a "longer leash" (STRANGLER also includes the only graphical decapitation to be found in any of these films).

Thanks for taking the time to re-post the entire comment; it's fascinating stuff. I feel very much a beginner, or outsider, when it comes to watching and commenting on these films. I've worked my way through 40+ this year (Rialto and non-Rialto combined), but always have a nagging feeling that there's a great deal of context and film history surrounding them of which I'm not yet aware.

DeleteAfter discovering the Giallo a few years back, I didn't think I'd ever run into another genre that was so captivating, so stylish, so pleasingly strange. The Krimi has certainly fit that bill, and I'm thankful that I found it.

Please continue to post whenever you feel like it--I'm hoping this site can be a kind of clearinghouse or resource for all things Krimi- and Giallo-related. The more perspectives the better.

And I was able to see THE STRANGLER OF BLACKMOOR CASTLE, though only on the less-than-acceptable US DVD. That DVD is badly dubbed, cropped to the wrong aspect ratio, and taken from a muddy print. I'm ever hopeful that more high-quality English-friendly releases will make their way to fans (I did spend the year purchasing the German EW box sets one by one, even though some of the movies contained within them didn't have English options). The German release of Vohrer's SCHOOL OF FEAR that came out this year was also a welcome surprise, as it contains 7 minutes of footage missing from the previous US disc. It was great to see it complete and be able to write it up finally.

Cheers on more comments, and more Krimi watching!

Also, re: Reinl's relation to violence (esp. violence involving his then-wife Karin Dor), there's an interesting observation in this review of Reinl's THE CARPET OF HORROR:

Delete"The more I watch movies by Reinl the more I am fascinated by the fact that he just seems to thrive on bondage scenes. Most of his films have characters strung up and often abused or tortured; and a lot of times he seems to share a morbid delight on inflicting this kind of torture on his real-life wife."

CARPET OF HORROR also came out on Blu-ray this year.